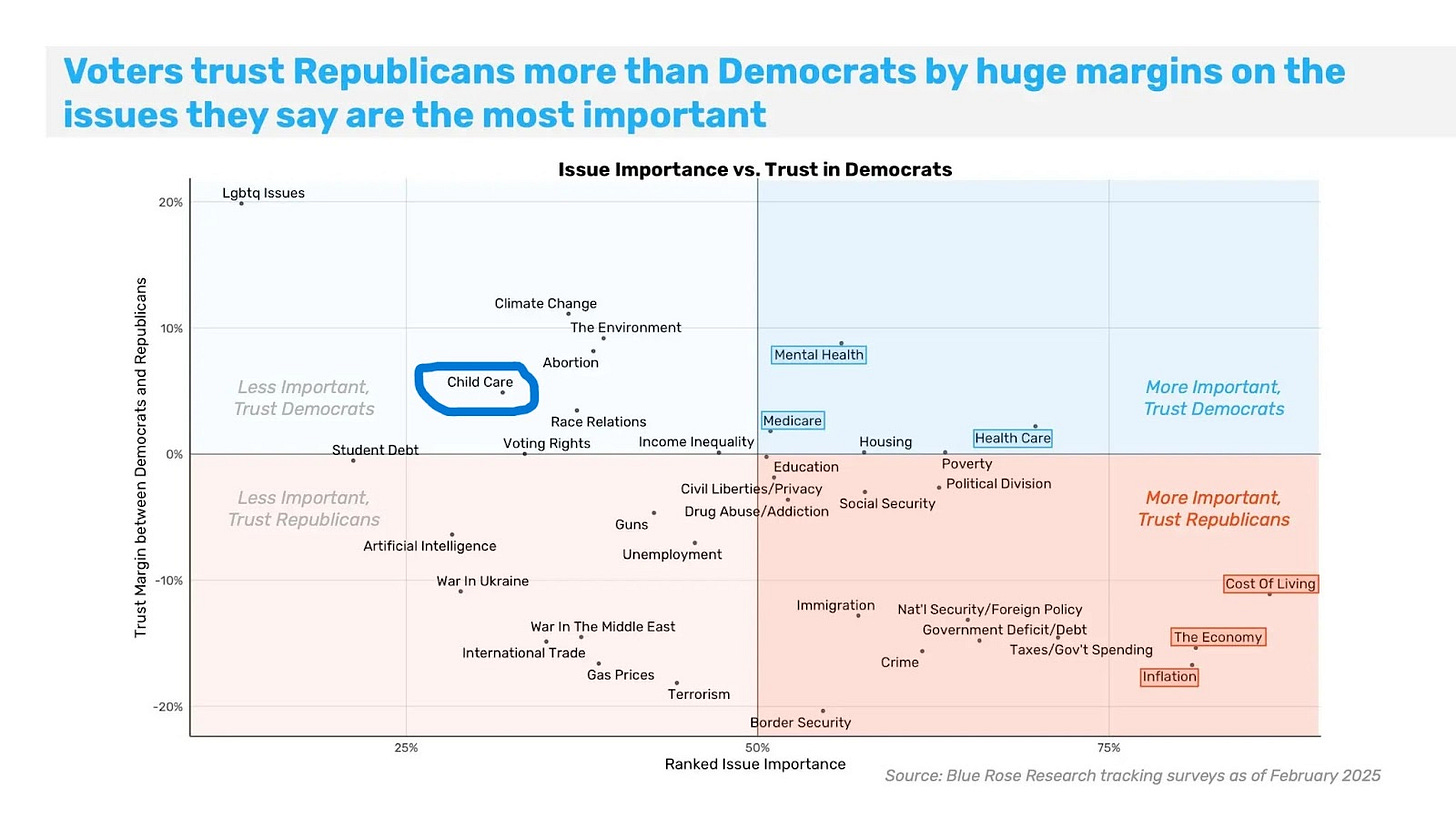

There’s a chart I’d like to share with you that’s been living, as they say, rent-free in my brain for the past two weeks. It comes from a conversation The New York Times’ Ezra Klein had with Democratic political analyst David Shor. The chart shows polling of 2024 voters on different issues, comparing both which party the voters trusted more and also how important the issue was. You’ll see immediately why this caught my eye:

Child care is rated the fifth-least important issue out of more than 30 options.

In one sense, this isn’t at all surprising. I wrote an Early Learning Nation article back in March 2023 entitled “Voter Support for Child Care is Sky-High Yet Butter Soft,” where I noted:

One unaddressed political problem is that voter support for child care is exceptionally soft: it doesn’t actually create incentives or consequences for elected officials. Until the sector reckons with that reality and comes up with a strategy to combat it, we will struggle to make true progress. High poll numbers are nice but, until they harden, can threaten to lull us into a sense of complacence that we’ve got the public on our side.

In political communications terms, child care—like many children’s issues—suffers from a problem of salience. Salience is a near-synonym for importance, but it carries more implications. Specifically, salience asks the question ‘how much does this issue impact voters’ behavior?’ Scholars suggest that salience encompasses both how much attention voters (and the media) give an issue and how much weight they assign it when making decisions.

Yet in other ways, the child care result is actually quite concerning. Child care has received steady media attention from nearly every local, state, and national outlet in America; it is a challenge that crosses partisan lines; major business groups like Chambers of Commerce talk about it regularly; and while child care wasn’t a huge flashpoint in the 2024 presidential race, to my read it came up significantly more often than even public education. So what lessons can we draw from this chart of doom? I’ll offer a few:

0. Don’t overreact to one data point.

OK, maybe this is cheating, but I do think a caveat is in order. It’s notoriously tricky to figure out what polling numbers are actually telling you -- lies, damn lies, and statistics, as they also say. After all, “cost of living” was the number-one issue voters cared about, and what is child care if not a cluster bomb dropped in the middle of families’ cost of living? What’s more, “child care” is arguably not a universally understood term in a world where there is also regular usage of “early childhood education,” “daycare,” “pre-K,” “preschool,” “after-school,” and so on. That said, I also don’t think we should underreact: as I said, child care’s low political salience has already been established. This data can be seen as a confirmation that even increased media attention isn’t truly moving the needle.

1. Child care’s direct constituency is too small; time to broaden the tent.

There are somewhere around 30 million individual parents in America with a child aged five or below. About a third of these families utilize a licensed child care program. Roughly 156 million people voted In the 2024 election (and the total U.S. electorate is ~260 million). Even if you want to assume an unrealistic scenario where every single parent of a young child voted, they would be dwarfed by their counterparts. And of course, with birth rates declining, parents’ relative share of the electorate will only be shrinking.

This means there is a desperate need to broaden the constituency. The lowest-hanging fruit, as I’ve written before, are parents of school-aged children. After-school and summer care are massive pain points, there are tens of millions more parents of elementary-aged kids (to say nothing of those in middle and high school), and those parents are not busy chasing toddlers around the house. There’s a common refrain that one problem child care has is that it’s a temporary challenge -- just grit your teeth and bear it ‘til Kindergarten -- but if you rightly extend thinking about child care through the schooling years, it’s a decades-long challenge.1

That said, I also think there is a fruit hanging not much above school-aged parents: grandparents. It’s somewhat remarkable to me that no one has (to my knowledge) poured gobs of money into organizing grandparents to rally around fixing child care and holding elected leaders to account. It’s not like they aren’t hearing about their kids’ child care struggles on the regular, or being called in to support when external child care breaks down. If we want to boost child care’s salience, release the grandparents!

2. Siloing child care is unhelpful.

Parents, like all people, are rarely single-issue voters (or if they are, that issue is far more likely to be abortion than child care). Despite Kamala Harris having an objectively more fulsome agenda around family policies like child care, the child tax credit, and paid leave, exit polls suggest 59% of fathers with minor children, and 47% of mothers with minor children, voted for Trump.2

I’ve also written about this before, but parents do not experience their lives like a buffet: child care over here, paid leave there, health care by the soup, job quality on the dessert tray. If child care hangs out on an island, it’s unlikely to garner enough support to become an issue of consequence -- and I mean literally an issue in which politicians feel an actual consequence, in either direction, for acting or not acting.

We have to do a better job of creating a superstructure into which child care fits: a vision of a country where family life is not only affordable, but where parents can go to work every day feeling good about where their kids are and about their development, return not so exhausted they have no capacity for quality family time, move through their days in solidarity rather than competition with others trying to navigate the wild ride that is parenthood. Universal, abundant, pluralistic, ideally-free child care is a key pillar of that structure, but it’s not the whole structure.

To put it more pithily: a pro-family agenda may succeed where a pro-child care agenda has faltered.

3. Child care still needs to make the private-to-public jump

A final lesson that I think is hiding in Shor’s chart is how child care is still in the early stages of making the private sphere-to-public sphere jump. By that, I mean there are a set of challenges we consider in the private individual realm, and a set we consider appropriate for public response. These are not static categories, and the shift is generally considered by political scientists like Elaine Kamarck to be a prerequisite for major societal and public policy responses. A canonical example Kamarck offers is smoking: long considered a personal choice, smoking has successfully transitioned into being a public issue to the point where it is banned in nearly every public place and few people object. Transportation or dating struggles, on the other hand, are generally considered to be a private problem.3 Obesity is currently somewhere in the middle. So is child care.

I’ve explained how child care’s sordid history in America has led it to be hammered down for decades as a private issue (with a side of reluctantly offered welfare for poor families).4 That ship has been slowly but steadily turning in recent years thanks both to current events and intentional advocacy, organizing, and pop culture-influence efforts. There is still much more to be done to bring child care fully into an integrated sphere where society comes alongside parents to support their freedom and thriving, as opposed to being seen as two poles in opposition.

To wrap up, I want to say again about Shor’s analysis that one piece of data is exactly one piece of data. Caveat emptor. That said, those of us who care about family flourishing and about winning the child care and family policy system kids, parents, and educators deserve must be clear-eyed: we need to step up our salience strategy.

Of course, parents frequently fall into both camps: roughly as many parents have only children under the age of five as parents who have at least one child under the age of five and one school-aged child.

There’s no single explanation for this result, but legal scholar Deborah Dinner has offered in an essay that Trump “was able to control the working families discourse by linking it to related cultural tropes: a blustering, misogynist masculinity, gun rights, Christianity, ‘law and order,’ and rugged rural values.”

There are exceptions, naturally; and who knows, will government marriage incentives be followed by government matchmaking services?

As Deborah Dinner writes later in her piece, the day after Richard Nixon vetoed the Comprehensive Child Development Act, he signed tax legislation that included a deduction for child care expenses. In doing so, “Nixon had, in these two successive actions, entrenched the bifurcation of childcare policy into public, government-funded childcare for the poo, and privatized, commercial daycare for the middle class. Childcare policy thereby accommodated the growth in mothers’ labor-market participation while protecting the ideal of family autonomy and private child rearing.”

As the nation moves more and more toward the privatization of education - child care - specifically infant and toddler care will become even more at risk. America is clearly unwilling to lift child care fully out of enslaved labor.