If you know one thing about modern child care history, it’s probably Richard Nixon’s awful veto of the 1971 Comprehensive Child Development Act. That legislation would have started to create a nationally-funded, locally-run network of child care programs, and it passed both houses of Congress on a bipartisan (though not overwhelming) basis. But there’s a sorry episode you probably don’t know about which I think helps explain the politics of child care even better: follow me, if you will, into the headache-inducing failure that was the Child and Family Services Act of 1975.

First, let’s set the scene: Gerald Ford was president, and Democrats had sizable majorities in both the Senate and the House. Walter Mondale (who would be tapped as Jimmy Carter’s running mate the following year) continued to be the child care champion in the Senate, John Brademas in the House; both men had led the 1971 push. Given the economic situation and an unfriendly president, there was little chance of getting anything transformative past a veto. Compared with earlier child care legislation, as Sally Cohen has written in her history of U.S. child care policymaking in the last third of the 20th century, the Child and Family Services Act’s “authorization levels were lower,” and it was generally a watered-down version of the ‘71 bill. Despite this, “conservatives launched one of the most devastating attacks on federal child care legislation.”

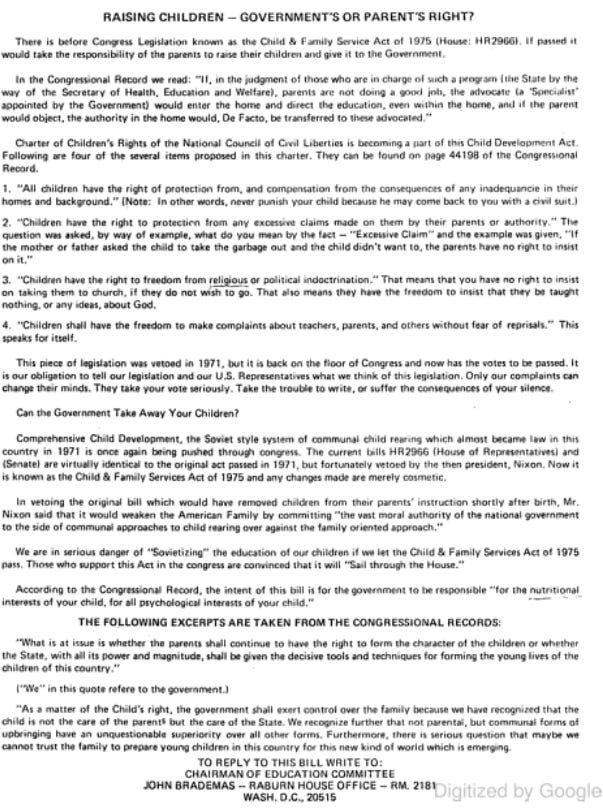

The attack came in the form of an anonymous flyer that leveled hysterical and false charges about what the Act would do. To this day, no one knows (or at least it has not been reported publicly) who originally created it.1 You can read one version of the flyer for yourself:

It’s a bit hard to read because this is a digitized version of an old document, so let me transcribe a few highlights:

“In other words, never punish your child because he may come back at you with a civil suit.”

"The parents have no right to insist on [the child taking out the garbage]."

"You have no right to insist on taking [the child] to church."

"The government shall exert control over the family because we [the government] have recognized that the child is not the care of the parents but the care of the State."

Add in a healthy dash of Soviet and Chinese Red Scare to these lies, and we were off to the races.

It’s difficult to overstate the degree to which this flyer and its copycat cousins went a 1975 version of viral. As Cohen recounts, “Mondale had to hire two additional staffpersons to handle the 2,000 to 6,000 letters he received daily in opposition to his bill.” Conservative publications like American Opinion took the scare tactics and ran with them, producing some truly amazing political cartoons in the process:

Mondale, Brademas, and their allies tried to fight back against the misinformation. Even many groups critical of the legislation said publicly that the flyer’s attacks were baseless, and that they’d rather have a debate over what they saw as the bill’s actual problems. The episode drew the attention of nearly every major newspaper in the country.

Again: This entire kerfuffle was happening over a pretty modest piece of legislation, only in committee at the time, that was significantly weaker than the bill which Congress actually passed four years earlier, and which did almost nothing that the flyer suggested it did! But you know how easy it is to put the misinformation genie back in the bottle. All the newspaper headlines and floor speeches and distributions of factual background information barely made a dent. Not only did the Child and Family Services Act go nowhere, Cohen notes that Brademas himself said “the intensity of the anonymous campaign ‘made it very difficult for anyone to get close to this legislation for some time.’”

Stepping back, one result of the 1975 debacle was to cement in the minds of wide swaths of conservatives the ground Nixon had begun paving with his veto: the government and the family stood opposed, and any attempt to support families in their child care needs—beyond limited welfare for the very poorest—constituted an assault on the very heart of American family life.2 If ‘71 was the earthquake, ‘75 was the aftershock.3

This was a battle that Democrats and child care advocates lost, and lost badly. And that matters. As Josh T. McCabe, who directs the social policy team at the Niskanen Center think tank, wrote in his 2018 book The Fiscalization of Social Policy, “The last decade [has brought among scholars]…a new appreciation for the process through which policy legacies exert a cultural influence that shapes later actors attempting to making significant policy changes.” McCabe goes on to show how what he describes as “benchmark events”—critical periods in policy development on a particular issue—exert a strong downstream influence by establishing dominant “logics of appropriateness” in terms of who should benefit from a given policy arena and why.

When I say that we need an intentional culture change strategy around child care, then, this is part of the reason: while attitudes have certainly shifted some in the intervening 50 years, there are still an awful lot of people—including lawmakers—who believe universal child care entails turning Uncle Sam into Big Mama.4 Those of us who back a child care system that works for all children, families, educators, and communities have a lot more resources at our disposal now than we did in 1975, and we need to deploy those resources to undo an underappreciated legacy of a largely forgotten episode that still shapes American society today.

The most anyone was ever able to track down, at least that I’m aware of, came from a Houston Chronicle reporter who wrote in an article that the flyer originated from a religious revival event in Missouri and then spread much like a “chain letter” throughout the South and then nationwide.

As scholar Nancy L. Cohen has written, “Consider what [the 1975 flyer] stirred up in one Bible Belt state. The flyer made its way to the Oklahoma chapter of Women Who Want to be Women, a recently formed anti-ERA fundamentalist women’s group. Fantasies about forced child care were already familiar to them from a popular anti-[Equal Rights Amendment] pamphlet written by the national founder of the Four Ws. (The so-called Pink Sheet deemed the ERA “the most drastic measure in Senate history” and said it would, among many other horrors, force mothers to put their children “in a federal day care center.”) The Oklahoma Four W’s made killing national child care legislation their first political campaign, and they successfully lobbied the Oklahoma City PTA council to oppose the bill.”

Technically debate around the bill stretched from its introduction in late ‘75 into the spring of ‘76 -- hence the dates on some of the newspaper articles -- but I’m shorthanding based on the Act’s introduction date.

And even some who still think it would make us communist! Tennessee Sen. Marsha Blackburn tweeted during the 2021 Build Back Better debate: “you know who else liked universal day care” followed by a link to a 1974 article about the Soviet Union’s child care system. Red Scares are evergreen, I suppose.